Written by Mark L. Staker Published: 08 June 2015

Mark Lyman Staker serves as a Senior Researcher in the Church History Department of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and has been

involved in historic sites restoration for more than fifteen years. His Hearken, O Ye People: The Historical Setting of Joseph Smith’s Ohio Revelations

(2009) is a landmark study placing the revelations received by Joseph Smith

in historical perspective. He holds a Ph.D. from the University of Florida in

cultural anthropology.

Introduction

Travelers complained in letters and reminiscences how during wet months of the year the hard clay became deep ruts, supporting treacherous puddles on the Harmony Turnpike.1 Despite their complaints, the turnpike was the quickest route from western New York to the urban areas of southern Pennsylvania and the thoroughfare was always busy. Silas Gildersleve wrote his family on September 18, 1823, after traveling the turnpike, and noted how although they had terrible weather, he, his wife, and his mother-in-law managed to travel the road “as well as Could be Expected.”2 In the latter part of October 1825, the fall rains would have made the road particularly dangerous where it descended into northeastern Pennsylvania’s Susquehanna Valley. Winter approached, and one long-time resident, fifty-five-year-oldJosiah Stowell had a wagon full of men from the vicinity of Palmyra, New York, he was bringing to work in Harmony Township before they could no longer dig the frozen ground. A successful farmer, sawmill operator, and grain trader, Stowell hired the men either because he “had heard something of a silver mine having been opened by the Spaniards” or “an old document had fallen into his possession,” which “minutely described” the spot where a mine had existed in that valley. He and others had already searched the spot with hired hands, but he was returning for another effort with a new workforce to help him find it, including Joseph Smith Sr. and nineteen-year-old Joseph Smith Jr. This group of men left the Stowell farm heading southwest out of South Bainbridge, New York, crossing the Susquehanna River at the bridge leading into Harpursville, continuing south through Colesville by climbing Cole’s Hill past Badger’s tavern on the west side of the road at the crest, then dropping down the other side sliding toward the shallow Susquehanna River where the Windsor Bridge Company had earlier that year finished a toll bridge precluding the need to cross it using a ferry, and finally rattling down the Harmony Turnpike toward Pennsylvania into what they called the Endless Mountains.3

Four miles south of Colesville, the work party passed the Stow Cemetery, a small collection of burials abutting the east side of the road that would have caught their attention. Two of the ominous headstones at the edge of the turnpike were for Joseph Smith, who died on March 10, 1792, and Josiah Stow, a local farmer and grave robber, who died on April 2, 1820, the latter not to be confused with Josiah Stowell. The modest headstones the men could see as they traveled were made by stonemason J. W. Stewart, known for years as “Coffin Man.” But it was Oliver Harper’s large, ornate headstone just to the south of the two simple ones that would have likely been the focus of any discussion the men had with its neatly chiseled inscription announcing Harper had been robbed and murdered the previous year on March 11, 1824. The headstone, made by “Eclectic Man,” included visual symbols from Harper’s life.4

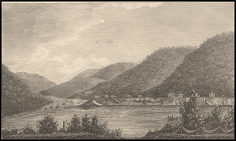

As the group rattled closer to Harmony Township, they traveled the last section of the turnpike in an experience described by a later newspaper reporter as like “being rolled in a barrel.” He insisted the turnpike could “guarantee the traveler a shaking he will not forget in a month.” But the reporter acknowledged, “And what is the one thing that would atone for so many inconveniences? The scenery, sir! The scenery!”5

The wooded mountains rising from the landscape were stupendous. In 1825 it had been eight years since Joseph Smith Jr. and his father left the green mountains of Vermont for the more open landscape of western New York. The massifs were reminiscent of their Vermont environs. When the Harmony Turnpike crossed the Pennsylvania state line, the Allegheny Mountain foothills began their gentle rise. The pinkish purple blossoms of Jo Pye weed along the road had long since faded, and now the bright yellows of the towering chestnuts in the river floodplain, the muted browns of the oaks leaning over the road, the brilliant reds of the maples in groves on the higher, south-facing mountain slopes, and the deep greens of the six hundred year old hemlocks on the north facing mountainsides all began to rise and fall in a pattern familiar to Vermont emigrants.

As the turnpike squeezed between the mountains, the rough road slumped into the Susquehanna Valley descending toward the river bend with its consistent early morning fog and faint smell of wet earth. The turnpike crossed the river at the bridge into Lanesville where it continued south past what locals called the “Vermont settlement” on Tyler Road. The bridge’s loose stones were worked out of its walls the previous spring when Jason Treadwell, a local sandy hair, red bearded, cross-eyed prankster accused of murdering Oliver Harper, had frantically pulled them out searching for a hidden four hundred dollars he claimed was placed there. Treadwell sobbed when he couldn’t find the money, claiming it was stolen by an accomplice in robbery.6 The travel party likely paid little attention to the bridge that had Martin Lane’s tollgate on the other side, as they followed the bend in the river veering right at the turn onto Oquago Road—a road described by travelers as a narrow, rut-filled, tree-root- bound path running west between Oquago Mountain and the north bank of the Susquehanna River. The Stowell work party went a little over a mile and a half west on Oquago Road where a narrow footbridge on the west side of a small cemetery connected the families across the river and marked the beginning of the farm of Vermont emigrants Isaac and Elizabeth Hale.

While helping Josiah Stowell look for the rumored Spanish silver, Joseph Smith Jr. took lodging on the rocky farmstead of the Hale family—an unproductive lot running from the riverbank north to Oquago Road above the floodplain. The farm continued north of the road through a section of swampy ground known in local dialect as a “swaily,” and onto the mountainside with a large stand of ancient hardwood forest thinning at the top to provide a good view of the surrounding area at a spot known in local dialect as a “keek” from the Scottish for a peep or quick look.7

It was on this largely unimproved farm that Joseph Smith Jr. first met Isaac and Elizabeth Hale. A traveling minister, who preached in the Hale home, remembered Isaac Hale as “a shrewd, witty man”; one of his neighbors identified him in court testimony the previous year as “old Mr. Hale,” but most of his neighbors would have recognized in him a devoted husband and father, a devout Christian, and a developed backwoodsman who preferred solitude and independence, even in his request to be buried apart from his neighbors.8 Isaac’s wife, Elizabeth Lewis Hale, may have gone by Betsey.9 She could sign her own name in a careful, practiced hand, and her neighbors found her an intelligent, enjoyable conversationalist.10 But she remained firmly in the shadows of her husband. Joseph Smith left no record of what he thought of the Isaac and Elizabeth Hale farm and recently expanded home when he first encountered them at nineteen. But his response to their home may not have been quite as exuberant as was his mother’s when she visited it three years later, since she was more attuned to its elaborate character and what it did for one’s place in the community. Ever bent on elevating the situation of her family, Lucy gushed about the Hale home in a later reminiscence when she noted “the ma[n]sion in which they lived [was] a large neatly finished frame with <every> convenient appendage necessary.” Their mansion, she recalled, was “pleasantly situated,” and it stood on “an extensive and well cultivated farm.”11 Not only did they live in a home full of comforts, according to Lucy, but she seemed to believe their circumstances added to their moral standing. She noted they were “a lovely intelligent and highly respectable Family,” and their home and farm “did honor to the good taste of the intelligent proprie<tor>.”12 The Hale mansion fit into a class of homes described by Early American historian Richard Bushman as “middling mansions.”13 Their recently expanded home helped give the Hale family a level of vernacular gentility that had recently found its way into the remote valleys of the Endless Mountains. It was built during a time of spiritual renewal for the Hale family, and it had become an outward sign for them of what they were hoping to develop described as “an inward grace.”14 Joseph first met Isaac and Elizabeth Hale’s third daughter in their comfortable home. “Twas there that I first saw my wife,” he recalled.15 This daughter, named Emma but called Emmy by her friends, was described by a neighbor as “a pretty woman; as pretty a woman as I ever saw.”16 She was eighteen months older than Joseph, and although the Hales had another daughter also living in the house, blued-eyed and fair skinned Tryal Hale who was a little less than a year younger than Joseph, the young man was drawn to brown-eyed, dark haired, olive complexioned, and noticeably intelligent Emma. He “immediately commenced paying his addresses to her.”17 Emma’s parents saw in her the same example of grace, refinement, and gentility they hoped their home could give.

Joseph courted Emma Hale while she lived in her parent’s home, and he hoped to marry her in its parlor, as was custom in the valley. But her father “would not suffer us to be married at his house,” Joseph noted. This meant Joseph was “under the necessity of taking her elsewhere.”18 Not long after Joseph married Emma, however, the two lived briefly in the home as Joseph began his work and prepared to move into his own home. Joseph began his first efforts translating the Book of Mormon in the Hale home and found protection as he began his work. Understanding the physical setting of the Hale farm and its mansion, helps us to not only better place the events of 1825-1830 Mormonism within their physical and cultural setting, but also enlarges our appreciation of the Isaac and Elizabeth Hale family.

Isaac and Elizabeth Hale Move from Vermont to Pennsylvania

The Move from Connecticut to Vermont and Back

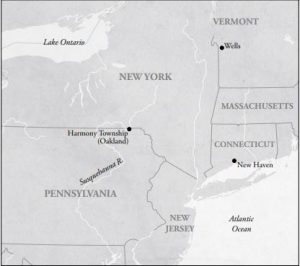

The Hale farm began with Isaac Hale. He was born March 21, 1763, in New Haven, Connecticut, to Diantha Ward and Reuben Hale. After his mother died and his father remarried, Hale joined his maternal grandparents Phebe and “the enterprising Arah Ward, mill-builder and pioneer,” in Waterbury, Connecticut. Arah began to build a second, larger home until the dam to his mill gave out and destroyed his home and livelihood. Along with their sons (and Hale’s uncles) David and John Ward, Arah and Phebe Ward took ten-year-old Isaac and set out on a 176-mile journey to establish a new life in Wells, Vermont, where Arah purchased a mill site in July 1773.19 The following summer the Wards donated ten acres for a Congregational church, and David Ward served as the Reverend.20 William Cowdery Sr. (whose grandson Oliver was born in Wells) became the deacon in their church.21

Isaac helped his grandfather build a gristmill in Wells and run it until the Revolutionary War transformed their community. He was only twelve when news arrived of the first skirmish on the Lexington Green in Massachusetts. In 1777 fifty-nine-year-old grandfather Ward was killed at Addision, Vermont, while fighting against General Burgoyne and a large Native American force that had mostly come from the Susquehanna Valley in northern Pennsylvania after 1,200 American soldiers burned their villages and massacred their families.22 In 1780, when Hale was seventeen, he enlisted, along with his uncle David, to fight under Colonel Ebenezer Allen’s command as they sought to prevent Canadian military raids into the Mohawk Valley. Hale’s brief tour of duty ended eight days after his enlistment when the younger soldiers returned home without seeing action and the seventeen-year-old private was released from service.23

After Hale returned home from military service, he inherited all of his grandfather’s estate with the stipulation that he was to take “into his Care his Grandmother Phebe Ward in her old age, to keep and provide for during her life, to free her from all or any cost to this State.”24 Despite the presence of his uncles, Hale inherited both the property and responsibilities of a son. 25 His new role suggests how much he had become a “Ward” rather than a “Hale” in both outlook and position. Isaac’s grandmother may not have lived long afterward, however, or others agreed to take over responsibility for her care, since in 1784 Hale deeded the property earmarked for her care to his uncle David Ward, and he left for Connecticut.26 Hale may have returned to his birthplace to reconnect with the rest of his Ward relatives, particularly his uncles and aunts Jesse and Eunice Ward Cady and Daniel and Tryal Ward Curtis, since he later named two of his children Jesse and Tryal. He may have also visited his father, Reuben Hale, or older brother, Reuben Hale Jr., both veterans of the recent war, or with his sisters Naomi and Antha (Diantha) Hale. They all still lived in the area along with stepsisters.27 Despite a possible visit with his Hale family, however, they never connected or maintained long-term ties. Four of Isaac’s children were named after his Ward relatives, an additional three were named after Elizabeth’s Lewis family, and the youngest child, their son Reuben, was more likely named after Elizabeth’s brother Reuben Lewis than Isaac’s brother Reuben Hale. The only child of Isaac and Elizabeth that did not inherit the name of a family member was one of their daughters, Emma, who was born when her parents had a special relationship with a prominent family within the American gentry who may have influenced the name selection.

The Move West

In 1785, Isaac Hale stepped into the headquarters of the Susquehanna Land Company. Land speculators there aggressively promoted property along the Susquehanna River, advertising as far away as Germany seeking young, ambitious settlers to buy their land. By the time Hale entered their office, potential clients in the region knew of troubles with Susquehanna property deeds. The Susquehanna Land Company bought its land from Connecticut, but Pennsylvania also claimed ownership and bloody skirmishes—the Pennamite Wars –erupted between “Yankee” and “Pennsylvania” settlers, and the most recent conflict was still not fully resolved. Vermont war hero Ethan Allen, who helped create Vermont from New York and New Hampshire, had agreed in late 1785 to travel there the following spring with a detachment of Green Mountain boys and create a new state from the land.28 Although Allen never followed through, Hale may have become caught up in this Vermont enthusiasm. Whatever the ultimate motivation for Hale’s decision to ignore the controversy, “after having worked one summer in Connecticut, he concluded to try ‘the West.’”29

Hale traveled from Connecticut along the newly opened turnpike to southwestern New York until he arrived at Ouaquaga village or “Old Oquago,”which straddled the Susquehanna River four miles south of what would eventually become Colesville, New York.30 Major General John Sullivan’s soldiers had already burned Ouaquaga to the ground and massacred hundreds of Onondaga tribal members and recently settled Tuscarora families before Hale arrived, leaving corn in the fields, apples in the orchards, and tools scattered about the ground. Some of the survivors of this massacre fled north to Canada and fought for the British in Vermont.

Among the ruins, Hale met Daniel Buck, an army surgeon and officer during the recent war. Major Buck’s father had placed him with the Onondaga people when only eleven years old to learn their language. This was part of the evangelist Jonathan Edwards’ strategy to rear missionaries prepared from their youth to take Christianity to Indian villages in southwestern New York and northern Pennsylvania, and Buck lived with the Onondaga, or “People of the Hills,” for ten years before the start of the war. “He was considered one of them but not in all things.”31

One day Buck tried to follow some of the Onondaga men south as they slipped away to gather salt at a hidden spring. As he entered into a valley where the river turned and headed west, Buck was caught by the Onondaga men he followed and his life threatened. This ended his attempt to find their salt source, but he was certain it was in the valley at the bend of the river about two miles below the New York State line. Buck was avidly interested in finding salt mines or springs essential to hunters preserving and shipping meat downriver, and his travels in the area gave him a rare familiarity with a region little understood by outsiders.32

Early map makers of the region acknowledged their lack of information about the area by writing “Endless Mountains” across a large section of unmapped land without trying to include details they did not know.33 The name stuck and is still used for the region today. It drew from the King James Bible’s phrasing of a blessing given by Jacob to his son Joseph promising him blessings “unto the utmost bound of the everlasting hills” (Genesis 49:26). Among Joseph’s blessings, he was promised, “the chief things of the ancient mountains,” and “the precious things of the lasting hills” (Deuteronomy 33:13–17). These were the things Buck hoped to discover.

As the foliage colors warmed and deepened, Hale joined his efforts with Buck at Ouaquaga where he hunted for meat while Buck gathered frost-bitten corn growing unattended in the fields. He ground it for cornbread using an abandoned mortar and its companion pestle.34 Since Buck had a young family, including his small son Ichabod whom he had brought with him to the village, Hale must have been of considerable assistance.35 Buck and Hale interacted with the survey team active in the area and knew the land was surveyed and legally available.36 But shortly after becoming associates, the two men traveled south together over the New York border into the valley where Buck thought there was salt and where contested land claimed by the Susquehanna Land Company was inexpensive.

The Susquehanna Valley

Without a turnpike heading south from Ouaquaga, Buck and Hale took the Warrior Path, a narrow trail that followed the river south fifteen miles, and then turned west still following the river as it made a great bend through a narrow, crescent-shaped valley roughly 2,000 feet wide—typically leaving just enough fertile land for thin farms on the north side of its banks—and running for less than thirteen miles before the river turned north and entered New York again. The Warrior Path was a major travel route created by Native Americans on foot as war parties moved rapidly through the region to control territory of interest to competing tribes active in the beaver fur trade.37 It also led to hunting grounds along the river’s tributaries.

The valley was essentially a hunting preserve, but there was a small settlement on the east end near where three apple trees stood that “formed the rallying point and headquarters of all the Indians in the neighborhood. As early as 1779 these trees bore the marks of great age.”38 It was here at those trees that some of Sullivan’s soldiers gathered to plan their raids on the nearby villages near “traces of an Indian village” on the north side of the river where Josiah Stowell’s workmen would later look for a lost silver mine east of what would become the Hale property.39 The rest of the valley had small campsites built along the trail hidden from view for use by hunting or trapping parties making their way through there.40

Early settlers referred to the place where the river entered Pennsylvania as the “east bend” and where it returned into New York as the “west bend,” while the entire river as it passed through the valley was the “great bend.”41 Although the valley remains officially unnamed, early residents along this great bend called it the Susquehanna Valley.42 During the twentieth century that name has generally come to refer to a much larger region that includes the entire river drainage system through upper Pennsylvania.

Hanna, anna, and honna were all English spellings for a word the Onondaga applied to local rivers, brooks, or creeks meaning “stream of water;” and susque was the English spelling of a word whose meaning is still debated but may have meant “muddy,” “roiling,” or “serpent like.”43 Since the river is rarely muddy except during flooding and is only serpentine when seen from the sky, it may be the Onondaga intended to suggest by Susquehanna the rough, roiling rapids frequently found in the shallow water.

During the earliest settlement period or before, the oldest and most commonly used name for the village where Daniel Buck and Isaac Hale first met, Oquago, was attached to the mountain where Hale settled. The word’s purported meaning of “place of hulled-corn soup” may have had reference to “several pits containing charred corn” Buck and Hale found near the ancient apple trees.44 No matter who named the mountain, that name permanently connected the Hale family and their mountain to the Onandaga people who lived there before.

Settling in Pennsylvania

David Hale expressed some uncertainty as to exactly when his father arrived in the Susquehanna Valley, dating the event to 1787 “or thereabout.”45 Buck and Hale were still up river at the Onondaga village in July of that year, but resources were quickly used up, leading them to follow the Warrior Path down river in the last months of that year or first months of the next.46 Hale wintered over in the valley, hunting to support himself and probably Daniel Buck’s family. The following spring of 1788 Jonathan Bennett built a log home, and David Hale recalled his father “bought an improvement of Jonathan Bennett.”47 Hale first occupied the farm that year, and Bennett settled with his two sons and two sons-in-law on a farm further downriver.48 If Bennett sold the land for what he paid for it to get out of a Susquehanna Land Company contract, Hale purchased 150 acres at twenty-five cents an acre.49 His log home, if Bennett built one like his father’s, was “constructed of yellow pine logs, hewed, and pointed with lime mortar, and lined on the inside.”50 Lime mortar was difficult to get in that remote area, however, and so the Hale home was probably mud chinked. In 1788 more white settlers came to the valley where Hale and Buck first met, and Daniel Buck became their first minister.51 He also established a congregation in the Susquehanna Valley where the Hale family and their Lewis in-laws attended his services.52 Jonathan Bennett served as the deacon of the congregation.53

Daniel Buck’s Congregational churches became the foundation of the religious community in the region. After several decades his congregations became Presbyterians, and these Presbyterians continued to play an active role in community affairs. They also developed a close relationship and identification with local Native Americans, perhaps in part because of Daniel Buck’s knowledge of their language and culture.

A local member of the Presbyterian congregation Zachariah Tarble was named after his uncle Zachariah who was captured by Indians as a young boy, along with a brother and sister, and taken into Canada where he became a Mohawk chief—a source of family pride.54 The younger Zachariah Tarble became a local Justice of the Peace and performed the marriage of Emma Hale and Joseph Smith Jr. His cousin Thomas Tarble married Daniel Buck’s daughter Mary and worked on Abel Stowell’s farm.55

Elizabeth Lewis: Background

After Isaac Hale established a farm, he returned to Wells to marry Elizabeth Lewis. Both Isaac and Elizabeth’s families came from the villages of New Haven County in Connecticut before settling in Vermont, which may have contributed to an emotional bond between the two. Isaac later described Elizabeth as “my esteemed friend and wife of my youth.”56 His perspective of husband and wife relationships is suggested in later trial testimony where Isaac recalled a neighbor had asked if he could “borrow a canoe to carry his wife and children down to Munsons [Tavern] where his wifes mother lived.” Hale responded, “I told him [the] canoe was not fit to carry women in.”57 Hale also shared the view of his contemporaries that a prospective husband needed to have a home and property prepared for his prospective bride to set up house before he could marry her.58 When Isaac left Vermont, Elizabeth was barely thirteen. Six years had passed since then. There was not time for courting between Hale’s return to Vermont and his marriage, and so during the six years he was away, he must have courted through correspondence. But the details of this courtship are not known.

When Isaac Hale was a young boy in New Haven, Connecticut, he was raised in a culture that promoted the search for gold. Even the elite where Isaac lived as a boy put resources into discovering precious metal. Ezra Stiles, the president of Yale College, lived near both Isaac’s maternal and paternal families when he recorded in his diary gossip he heard from Governor Trumbull, who, he believed, received it directly from governor John Winthrop the Younger himself, how Winthrop had found “plenty of Gold” in a secret gold mine in the nearby mountains and had made a gold ring he showed off to his friends. Stiles looked for Winthrop’s mine, but he only found and recorded what he believed was Hebrew writing chiseled into the rock above a suspected site by a couple of Jewish prospectors. Stiles also questioned traveling Native American bands about “Spanish gold mines” he heard existed along the Missouri River although nothing developed from it.59 Because Stiles never found the Spanish mines or Winthrop’s hidden source of gold, historians assumed his journal recorded a string of idle gossip and simply reflected the “folk beliefs” of the area. When a mine was accidentally discovered in 1985 in the same hills where Stiles thought it was located, the New York Times described it as “one of the richest concentrations of gold in North America.”60 What was thought to be idle gossip gathered by Stiles apparently was based on accurate information corrupted in the retelling.

While the early treasure lore Stiles collected may have been more accurate than much of the gossip about treasure typically shared during the period, his own search for and failure to find any gold was unremarkably average. Governors, academic leaders, businessmen, country farmers, and poor day laborers were all equally interested in finding hidden wealth in late eighteenth-century America and were equally disappointed in their failure to find anything of value.

British law encouraged prospectors to look anywhere for ore they chose as long as it did not disrupt “Houses, Orchards, Gardens, and Enclosures of Sugarworks.” The only other requirement of the law was that the finder pay a tax of one-sixth of any ore discovered.61 A loophole allowed for the tax-free discovery of buried coins, watches, jewelry, bars of metal, or other items not considered “ore.” The science of geology was not well developed at the time, and a folk treasure hunting tradition was imported from Europe and refined over more than two centuries that relied on supernatural means to find buried minerals and valuables.62 Prayer was also frequently used then as it is today in the search for lost things.

While the Spanish had discovered or appropriated gold and silver mines in Peru and other places in South America, the British had not been as successful, and so they turned to the more common way of getting gold—taking it from others. They most frequently got it from Spanish treasure ships.

His eventual father-in-law, Nathaniel Lewis, also lived in the area and was drawn into one of these searches. As “a native of Cape Cod” and a “South Sea man,” born to Mary and Gershom Lewis in Gilford, Connecticut, Nathaniel Lewis grew up in shipping and worked for a time as a sailor.63 He also lived on the Connecticut coast within view of Gardiner’s Island where Captain William Kidd purportedly buried stolen silver before moving to Block Island to negotiate his surrender for piracy. Kidd’s surrender put the entire coast in an uproar when the constables arrested him penniless and found less than 100,000 pounds sterling hidden with his friends for safekeeping. The public was sure he had four or five times that amount.64 Conversation in many country taverns centered on Kidd’s treasure and where it might be located and finding the hidden horde became a popular pastime. Some thought it might not have been buried on Block Island but on the nearby Thimble Islands just off the coast from Nathaniel Lewis’s childhood home and a few hundred feet from the much smaller Lewis Island. Despite a thorough search through the years of the islands in the vicinity, no one found Kidd’s silver.

Others speculated the silver may not have been buried on islands off Connecticut, but elsewhere in the country. Robert Quary, a new customs collector for Pennsylvania, captured two of Captain Kidd’s seadogs inland in Pennsylvania’s interior and spread the alarm that Kidd’s ship had been near the Pennsylvania coast. Quary was responsible for capturing smugglers, but this time he was convinced the men he captured were not just smuggling goods into Pennsylvania but had taken a detour somewhere to bury Kidd’s famous treasure in its mountains.65 Where, he did not know. Adding to the Quary speculation, Morgan Miles, a sailor arrested and taken to London to be tried for piracy, announced his captain, a man named Stratton, had buried a cache of silver at the mouth of the Susquehanna River before returning to England.66 These stories spread and were embellished with each new telling until there was a general perception that most pirates buried treasure, a perception that worked its way into fictional narratives largely unchallenged for centuries despite the lack of evidence.

As Nathaniel Lewis matured, he grew up in a Connecticut full of these stories. During the French and Indian War, he enlisted in New Haven, Connecticut, on March 22, 1762, in the 2nd Regiment 9th Company to fight under Captain Archibald McNeil who took part of his regiment to Havana, Cuba, to avenge Spanish involvement in the conflict. McNeil decided to head for Havana rather than fight local hostiles because Havana was “reputedly rich in booty.”67 The men captured ships and scoured the Caribbean in search of treasure, but when Havana fell in July 1762, and the hoped for treasure never materialized, McNeil’s Yankees sailed home with their only gold the amber skin of a sick and dying crew as a precursor to a serious yellow fever epidemic.68 McNeil remained undeterred and his family established a shipping business in the West Indies where McNeil’s son later became a pirate, or, as his family remembered it, “a privateer . . . which was then sanctioned by the government.”69 Nathaniel Lewis reenlisted in the navy at Sea Brook, Connecticut, where he served until July 22, 1763.70 But after his father, Gershom, died in Litchfield Township October 18, 1766, 27-year-old Nathaniel returned to Guilford to marry Esther Tuttle January 16, 1767. The newlyweds then settled six miles north of Litchfield in Goshen, Connecticut, where their first child was born November 19 or 20, 1767.71 They named her Elizabeth Lewis.

Elizabeth spent her early years in the midst of revolutionary sentiment. Her cousins named their son Algernon Sidney Lewis after the English philosopher Algernon Sidney who opposed absolute or divine right monarchy, and the Litchfield area became a central base for operations during the war where the Continental Army could rely on consistent support, store supplies, and keep prisoners of war.

Although Nathaniel Lewis enlisted for two separate terms during the French and Indian war, he enlisted again in 1775 as talk of revolution moved through Connecticut’s churches and taverns, and he served in the Continental Navy under Lieutenant David Welch when it was first formed until his enlistment expired on November 10, 1775.72 Since the navy was initially made of up merchantmen, Lewis may have been working in the shipping trade when he enlisted, or he may have presented his earlier navy experience at enlistment.

Elizabeth Lewis and Her Family in Vermont

In early 1776 Nathaniel Lewis transferred his home with its sixteen acres of land by deed to his commanding officer, David Welch, and he took his family north to the Green Mountains.73 Although the family may have traveled with relatives, Elizabeth Lewis at only eight-years-old still held significant responsibility during the move, helping her expecting mother with her brothers and sister—seven-year-old Nathaniel Jr., five-year-old John, and two-year-old Esther.

When the Lewis family arrived in Vermont, they settled in Wells Township. Although first chartered in 1761 as part of the New Hampshire land grants, the township was only recently organized by members of the Ward family and other local civic leaders. Connecticut investors promoted Wells land; and Connecticut settlers filled its mountain valleys. The Lewis family arrived among the earliest settlers, and they would have spent most of their time clearing land to make it productive. Although a large, level valley in the center of the township became Wells village, the Lewis family settled away from the village on inexpensive land on a rocky mountain top near the northeastern township line. Wells village in the central valley became the center of business in the township, while the northeastern portion of the town where the Lewis family lived did business in the village in neighboring Middletown Township where a booming settlement began to develop. Nathaniel and Esther had four more children as the family struggled to make a living in the hard scrabble of their new settlement. Nathaniel returned to the war briefly as he enlisted a fourth time and served in Vermont.74

Isaac’s son David later erroneously claimed his uncle Nathaniel Lewis had served with his father during the Revolutionary War and the two men together “had heard Ethan Allen swear, and so were not afraid of bears.”75 Hale had served under Ebenezer Allen, not the more famous Ethan; and it was David’s grandfather Nathaniel Lewis, not his uncle who was then not quite eleven years old, who had enlisted as a private in the army and served for eight days the year following Hale’s service.76 David’s mistaken memory may have been due to his recalling stories of his father’s involvement with Ethan Allen in an attempt to create a new state out of northeastern Pennsylvania.

After Nathaniel Lewis Sr.’s brief war service, he built a two-story frame house in the mountains to accommodate his growing family. The Lewis’s neighbors considered them “the poorest family in town,” and “about 1780 or a little later” when the first traveling Methodist preacher arrived in their region, he asked for the poorest family and the neighbors sent him to the Lewis’s door. Nathaniel and Esther Lewis became Wells Township’s first converts to Methodism.

After Nathaniel Lewis joined the Methodists, he “preached at his house” where he established “a small class” and became the class leader.77 His young son Nathaniel Jr. may have been his first convert. “Nathaniel became interested in preaching at a very young age of eleven and one-half years. His father was the leader of a Methodist class in their home.”78 Two of young Nathaniel’s brothers—John and Levi Lewis—joined several years later and also became heavily involved in Methodism. John soon became a minister to an established congregation.79 Elizabeth was among the “children” that did not join the Methodists then.80 While Elizabeth likely attended meetings with her family, until 1784 none of the Methodist ministers in America had been ordained, and so early converts such as the Lewis family continued to receive the sacraments from ministers of the Congregational Churches in their area. Isaac Hale and Elizabeth Lewis may have attended the same church services.

About this same time, another local citizen, Nathaniel Wood, who lived a little north of the Lewis family, was “excluded from the congregational church,” apparently because he “had gotten up a new system of religious doctrine.”81 “In the Wood families, and especially in Nathaniel Wood’s family, were some of the best minds the town ever had.”82 And they put their thoughts toward theology. Perhaps because their public discussions of religion differed from what was commonly accepted, their neighbors described them as religious agitators. During this period, the Wood family and some of their neighbors accepted Nathaniel Wood’s religious doctrines, and this growing group began meeting together in Middletown. A key element of their religious activity was the use of divining rods to receive revelation. They introduced a variety of doctrinal innovations through revelation, and they discussed using their rods to find treasure to finance a New Jerusalem.83 While it is not clear if Wood’s followers identified themselves by a particular name, it may have been something akin to “modern Israelites or Jews.”84 Outsiders called them Rodsmen.

While activities of the Rodsmen climaxed in 1801, the use of rods began in the late 1780s as Nathaniel Jr. approached adulthood and started courting. “A man came, first to Wells, then to Middletown, [and] introduced the hazel rod.”85 A number of these Rodsmen lived in Wells along the township line in the Lewis neighborhood, while most gathered in Middletown where Sarah Cole lived as she and Nathaniel Jr. courted.

Nathaniel Jr.’s brother John Lewis also met and married a relative of Sarah Cole in Middletown, Rhoda Hall. John and Rhoda married and joined the Methodists in 1789, then moved to Wells village where John became a Methodist preacher.86 Levi Lewis, a younger brother, also moved to “the village” where he operated a tannery and served as the Sunday School superintendent.87 As John moved from Middletown, Nathaniel Jr. continued to live there until he married Sarah at the Justice of the Peace in February 1790.88 Since his family noted Nathaniel Jr. “continuously” preached from the time he was eleven, it is likely Nathaniel preached Methodism in Middletown, but it did not go well as most families remained involved with the Rodsmen and Lewis saw few if any converts. It appears the Lewis men sided with the majority of Methodists that disapproved of divining rod use.89 Nathaniel moved to the Susquehanna in autumn 1790, and whatever existed of the Methodists in Middletown where he had lived quickly dissolved so that when Methodist preacher Laban Clark arrived in the town in 1799, the family of a Mr. Done was “the only Methodist family in the place,” and he was as deeply involved with the Rodsmen as were his neighbors.90 Perhaps the only reason Clark felt he could call Mr. Done a Methodist was because he convinced Mrs. Done to destroy her husband’s rod. The rise of the Rodsmen placed Methodists in the community such as Lewis in direct opposition to the local treasure digging culture that had been part of their Connecticut roots.

Isaac Hale was not a Methodist and not exposed to the same rural religious conflicts as has confronted the Lewis family. After Nathaniel Lewis married Sarah Cole, Isaac Hale arrived back in Wells sometime in the summer of 1790. He married Elizabeth Lewis on September 20, 1790, two months before her twenty-third birthday.91 Isaac and Elizabeth Hale took Nathaniel and Sarah Lewis, along with Sarah’s mother and her eight-year-old sister, Lurena Cole, and quickly left for Pennsylvania since they would travel over two hundred miles to their new home barely ahead of the winter weather using a small, single ox drawn cart to carry all their goods with those of the family members that accompanied them.92 When the Hale and Lewis families arrived in the Susquehanna Valley, winter had already arrived and the struggle for survival began. Nathaniel Lewis brought with him negative experiences with the Rodsmen and treasure digging culture, Isaac Hale arrived in Pennsylvania without the same conflict with his Connecticut roots.93

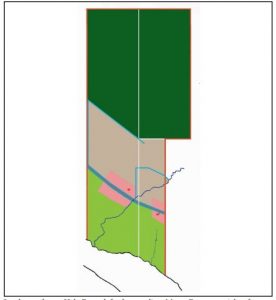

The Hale Farm

“Uncle Nate,” Isaac’s brother-in-law Nathaniel Lewis, and Nathaniel’s wife Sarah, squatted on a farm immediately west of the Hales on the north bank of the Susquehanna River ascending the foot of Oquago Mountain. The Hale and Lewis families began to make themselves comfortable on this land as the early settlers cut timber along the river floodplain that could easily be floated downstream to market without special equipment turning the bottomlands into rich garden loam. As the family worked, Connecticut and Pennsylvania soon resolved their competing land claims, and on April 4, 1789, the state of Pennsylvania sold the Hale and Lewis farms to George Ruper as part of a large tract of land that included much of the valley.94b Pennsylvania separated the valley from Tioga Township in March 1791, and made the entire valley Willingborough Township, a part of Luzerne County.95 As Isaac and Elizabeth Hale settled in Willingborough Township, Ruper sold most of his land to Tench Francis, a merchant in Philadelphia, who became their new landlord. The property boundary on the eastern line of the Lewis property and the western line of the Hale property cut through a Native American camp where a small band cooked food and made arrowheads. A hoe found at the site suggests it may have been more than simply a hunting camp since women worked there too. These artifacts were in the upper layer of the topsoil and Isaac Hale likely knew of an earlier Native American presence on his property.96

Near Ouaquaga village where Daniel Buck and Isaac Hale first lived, the new settlers developed an intense interest in buried wealth. When Doctor Richard Shuckburgh, Captain Borrow, and Silas Swart, some of the first white men to travel through the Susquehanna Valley, came through that region in 1734 under orders from the governor to search for mines, Shuckburgh looked over the region “like stout Cortez” hoping to find precious ore, but after he could not get local tribal leaders to share information with him he left, still certain they were hiding something.97 Shuckburgh is credited by many with later writing the words to the song Yankee Doodle, which if correct is somewhat ironic since the tune forYankee Doodle was used for a song in the first American comic opera The Disappointment that lampooned a Philadelphia merchant obsessed with buried pirate treasure.98

After Shuckburgh traveled through the Susquehanna Valley, settlers began to move into the mountains. Among them was a man named Josiah Stow, a deacon in Daniel Buck’s congregation, where Josiah Stowell would later also serve as a deacon. The similarities in name, location, and activities can easily lead to confusion between the two men. Stow settled on the outskirts of the Old Oquago village where Buck and Hale first met. Major Stow, shared the same military rank as Buck, and had consistent interaction with him. Stow recalled that as he began plowing he turned up numerous Indian burials that included “trinkets” of silver among which were the many silver nose pendants and silver ear disks worn by the earlier inhabitants.99 These silver artifacts were a distinctive element of traditional Onondaga dress. The daughter of Stow’s neighbor Elmore Russell found a large ring on her family’s property “supposed to have been once the ornament of some chief’s daughter.” It was later tested and shown to be “pure gold.”100 George Catlin, who grew up in the same valley and went on to become a famous painter of Native Americans in traditional dress, recalled of his own father’s experiences, “The plows in my father’s field were daily turning up Indian skulls or Indian bones, and Indian flint arrow-heads.”101

These grave goods may have encouraged the locals to look for raw ore on their property as well. The Onondaga and Oneida tribes had carried out extensive trade in beaver pelts for silver jewelry and other items from 1780–1821, and had become skilled silversmiths of their own work. They made nose pendants, ear plugs, gorgets, and crucifixes from European silver to adorn themselves and learned to work other metals. They sometimes buried brass kettles and other valuable metal not for later use in cooking but to protect their “treasure” from theft until it could be dug up and cut into decorative pieces for adornment.102 But there is no evidence they made any of their silver jewelry from locally mined ore. Nevertheless, white settlers developed their own mines in search for hoped riches. When Josiah Stow witnessed a land transaction of George Harper’s on April 18, 1789, Harper sold the land but specifically retained ownership “allways all gold and silver mines” on the property.103

Josiah Stow’s discovery of “treasure” in the Indian burials on his property became well known. Daniel Buck settled his young family in the middle of the Susquehanna Valley at “Painted Rock,” a site later known as Red Rock, because Native American inhabitants had used red paint to depict various figures, apparently turning the site into a ritual setting or sacred location.104 This was also the location of the “Indian burying-ground” in the area.105 The land at Painted Rock was not good farmland and before the railroad came through the area it consisted largely of a picturesque blend of massive freestanding rock formations and steep cliffs. There must have been a good mill seat in addition to an emotional connection between the sacred site and Buck’s Native American upbringing since Buck built a sawmill on the river there. But he may have also selected the site because of its sacred nature. J. B. Buck, one of Daniel’s grandsons, who was not there during the early years of occupation and appears to be reporting the memories of others, later suggested that what he described as the “first diggings” done in their area were at the Painted Rock site.106 He recalled his uncle “found the foundation of a house” on the island in the river at Painted Rock, where they targeted their initial digging. Buck’s neighbors later wrote of those foundations being evidence of “the presence and work of civilized man in it [the valley] before any known settlement of it.”107 The foundation was “grown up with trees” and only became evident when the land was cleared and plowed.108 The site has never been examined by archaeologists to evaluate if any evidence remains of what the men found.

It is possible these early diggings continued as time permitted but most of the focus in the valley was on settling the land and making a living. During this period, the government approved a plan to build new twenty-foot wide roads to replace meandering trails and increase access to the area. These roads would open trade to the Genesee Valley where men like Joseph Knight Sr. and Josiah Stowell could purchase large supplies of grain inexpensively and take their loads down to the river destined for the higher priced urban markets in Pennsylvania. Construction began in April of 1792, and by September the last of the five segments of the road was underway. Captain Charles Williamson, who became general land agent selling Phelps and Gorham lands in western New York, was hired as the road contractor. He in turn hired Isaac Hale the following summer of 1793 to make sure the road on this last segment was properly constructed from Colesville south through the eastern edge of Willingborough Township.109 The segment of road Hale supervised construction on became the Harmony Turnpike as it passed along the eastern edge of Oquago Mountain.110 But the side roads remained barely passable for years afterward. When the slave Sylvia Dubois was brought into the valley in 1803, she remembered the road that crossed the Hale property was rough, narrow, and nearly indistinguishable from the forest around it.111

None of the township’s thirty-six heads of household during the 1790s could make a living farming even after new roads tied their farms to major shipping routes. Just like the property of his neighbors, most of the Hale land was rocky, steep mountainside that took major effort to make arable. The flatter land along the river was initially used for family gardens, but after the famous “pumpkin freshet” of August 1794, when the river flooded and swept the settlers food supply downriver, settlers grew timothy grass and clover resistant to flooding along the river that provided winter hay for their livestock.112 Only a narrow strip of land on the ridge that followed the floodplain on the north side of the river-supported gardens.113

Life on the Hale farm remained difficult and isolated during the early years of settlement. Isaac and Elizabeth’s first child, Jesse, was born February 24, 1792. David followed on March 6, 1794. And Alva was born November 29, 1795. The Hale family had three boys ranging in ages from five down to one when British traveler Isaac Weld came down the river with some friends in November 1796. Weld’s group found poor families in the valley with empty pantries and few who could spare them even a little food.114 Many of the earliest settlements in the region started their existence with place names such as “Hardscrabble” and “Starvation”—names that were only changed in the nineteenth century as circumstances changed.

Although earning a living remained difficult, settlers continued to come. Robert H. Rose, one of the valley’s land developers, sought to attract immigrants from throughout New England and advertised in England and Germany, praising the wheat growing capabilities of the valley in newspaper advertisements. He claimed farmers in the valley typically produced twenty bushels of wheat per acre while many produced twenty-five bushels and some thirty bushels per acre.115 In reality wheat did not grow well in the valley. It was too wet and humid for a crop more susceptible to fungi than other grains.116 Barley suffered from similar challenges. Skilled farmers could grow a little of both wheat and barley when managed properly, but they never became major crops. Buckwheat grew best on the foothills and rising slopes of the mountains while oats and rye did much better in their valley than other grains.117 Settlers also grew corn, beans, pumpkins, cucumbers (they called these cow cumbers), potatoes, carrots, and turnips.118 But these could only be grown adequately on the north side of the river where the southern mountains did not shade the land in late fall or early spring, and it took more effort to turn the southern side of the valley into productive land than most of the valley’s residents were willing to give.119

The family’s struggles became marked during the winter of 1799–1800 when a severe winter hit the county and blanketed it in deep snow from November until May. This hard winter preceded a severe drought the following spring and on June 6, 1800, a frost hit the county that killed most crops. The drought and frost forced some local residents to walk for days trying to find enough food to feed their families.120 During the following summer of 1801, freezing temperatures and biting frosts again killed crops on July 26, August 5, August 25, and September 12–13. After two years of unseasonably cold weather many families were at a breaking point.121 They turned increasingly to the river for support.

During the early settlement years no one could live on their farming. “There was no means of earning money in the valley except by hunting or making shingles.”122 Wood was more plentiful than wild game and most of the settlers focused on it as their main commodity. Shingles were the first wood product sold because they were easily made without special equipment. Soon lumbering became a major activity along the river from as far north as Cooperstown, New York, and south beyond the Susquehanna Valley to the German settlements in Lancaster County. Men spent their winters felling trees and dragging them over the frozen ground to the river where they floated logs to sawmills powered along its banks. Sawmills quickly developed all along the river and the remaining waterway was filled with large arks and rafts taking lumber down the Susquehanna to Lancaster County where it was unloaded and carried in wagons 100 miles overland to Philadelphia. Some of it was even shipped overseas.

Lumber was also transported overland to the Delaware River about fifteen miles east of the Hale home where it was deposited until the spring floods carried the arks downriver straight to Philadelphia. Both options had their advantages but the Delaware was so popular for residents of the Susquehanna Valley that the village of Deposit eventually grew up nearby, and Hale Eddy, a spot on the river just below Deposit, became a staging area to prepare lumber for spring shipments. Most of Isaac’s sons were boatmen on the river during their younger days, and these men typically traveled in groups of three to six through the German settlements of southern Pennsylvania.123

While the valley soon produced carpenters, weavers, blacksmiths, and other craftsmen, Isaac Hale spent the majority of his time pursuing the other major profession available to the settlers—hunting and fishing. Meat, in fact, became the major form of currency in the region; when Isaac Hale and Nathaniel Lewis first settled the valley, “they exchanged meat for help on their farms,” and it became “the custom to give cattle, or ‘truck,’ as payment for work.”124 During those early settlement years, Isaac Hale could easily have been a model for Nathaniel (Natty) Bumppo, the “Leatherstocking” in James Fenimore Cooper’s novel The Pioneers: or, The Sources of the Susquehanna, which reflected a larger than life heroic hunter dressed in buckskin with Indians as his closest friends. Although the novel came out in 1823, the land, houses, and people Cooper described in his 1790s village also reflected life in early Willingborough. By the time Cooper published his novel, game was already harder to find, and Isaac’s profession had largely become a romanticized occupation of the past. It was an even more idealized distant memory when Isaac’s son David wrote about his father’s profession in the early 1870s. David recalled that his father specifically settled in the Susquehanna Valley because of the hunting opportunities the area offered. Whether it was Isaac’s first choice of occupation, or one of convenience, he “was a great hunter, and made his living principally by procuring game.”125 Because the valley had been a Native American hunting ground, Isaac Hale’s occupation put him in direct competition with the Indian villages in the region. But it also aligned him culturally with the local Native Americans since they considered it shameful for a man to do agricultural work; men were expected to hunt and fish.126

David recalled his father killed most of his wild game in the fall “when it was the fattest” and harvested about 100 deer each year along with bear, elk, and small animals. After cutting the meat into strips, he layered it and put it in long, narrow troughs of birch or maple, much like those used by his Native American neighbors, and an item he probably learned to make from them. He covered the meat with locally gathered salt to keep it from spoiling, holding it into place by heavy stones until snow covered the ground, and he could drag the meat filled troughs through the woods over the snow. Although most of Hale’s meat went downriver on arks bound for the Philadelphia market, or for export to Europe, his own family also relished game at their table.127 In Isaac Hale’s will he left instructions for the care his sons were to provide for their mother, specifically mentioning their duty to “maintain . . . Elizabeth Hale in a kind comfortable & proper manner during her life, find her meat, Drink Washing & lodging suitable & convenient for a person who so richly deserves kind treatment.”128 Hale was an attentive husband to the end.

While the “meat” he proscribed may have been a simple reference to food, Hale’s word choice in his mid-nineteenth century will also reflected the typical diet in the area. He did much of his hunting on Turkey Hill, across the river southwest of his home, and in the surrounding mountains. Food remains found on the Hale property include bones from turkey, mammals (such as squirrels), and small birds (such as passenger pigeons).129 A local historian recalled how “in some years there were millions of wild pigeons” available for food in the valley.130 The Hale family also made money by working leather into products and processing meat for other families in the valley.131 They left behind remains of antlers and animal bones made into handles and other implements to sell in the area.132 The Hale family did well enough relying on hunting that by the opening of the nineteenth century they began to assemble many comforts.

A Comfortable Log Home

Isaac and Elizabeth Hale had few expenses during their early years. Besides making no land payments, they grew their own food, and found resources primarily from their own farm or by sharing with neighbors. Most settlers along the Susquehanna also acquired some cash through selling their timber downriver which they could use to pay taxes, purchase window glass, nails, cooking implements, and other essentials. George Ruper owned their land only briefly after he acquired it from Pennsylvania. The Hales may not have even known he owned it. After Ruper sold his land to Tench Francis; however, the Hales clearly knew who owned their land.

In July 1798 Congress ordered a direct tax on the real property of Americans, known popularly as the “window tax,” this required that every family in the country have their home appraised. Near the end of that year, an assessor appraised the Hale family 15 x 30 foot log home as worth $26.133 The tax assessment noted they lived on a 150 acre farm owned by Charles Francis, using either an alternate name for Tench or that of an as yet unidentified son.134 Isaac’s brother-in-law Nathaniel Lewis’s family was also listed as occupying 100 acres of Charles Francis’s farmland just west of the Hale family that included a 15 x 28 foot log home and a log stable of unspecified size.135 Francis paid the tax for the land, not Isaac Hale or Nathaniel Lewis.

Details of the assessment and the value of the Hale log home in relation to those listed for others in the valley suggest Isaac and Elizabeth Hale had a comparatively large 900 square feet of living space in a 1 1/2 story log structure, but the building had no windows in the upstairs garret and few if any downstairs.136 The Hale family swept their garbage out the doors of their home into the yard as did all Americans during the late eighteenth century; this was not a sign of an unkempt family.137 The artifact scatter of broken ceramics, food scraps, and other items found around the Hale log home suggests the place where the family lived for approximately twenty years, and where Emma was born, originally stood on foundations repaired and reused for their later frame home. Documentary sources indicate the log home was moved and used as another residence, probably in the “yard” where outside work was accomplished east of the new home.138 Hale-period garbage scattered about the site included fragments of transitional creamware plates with a green or blue shell edge common from 1790–1810, the same period of manufacture for a dinner knife and two forks found in the same location.

The artifact scatter suggests a door in the log home faced east toward the work yard and toward a rock-lined well that still exists near the seasonal brook. The brook was the family’s primary source of water until they dug their well. A curved foundation wall on the west side of the home may have been part of the original log home cellar.

The partial cellar under the original log home was dug out and expanded to create a basement for the later frame home. In a small area were the basement was not expanded, few artifacts were found, which suggests that the original log home had a wooden floor made of hewn timbers or hand sawn lumber. A local slave recalled when she arrived in the valley, “already several people had moved to the neighborhood, had erected log houses, cleared the lands, and begun to cultivate fields and raise stock.”139 Each family built “a log-house covered with bark,” which differed from a log cabin in that the logs were smoothed with an adze to create straight edges, and the “bark” was generally used to enclose the upper portions in lieu of sawn lumber as was the case with the Hale family’s neighbor John Osterhout (as seen in the illustration).140

Despite the great insulating qualities and durability of logs, even when they were hewn and nicely shaped settlers considered them less refined than sawn lumber in frame homes, and they tried to improve the look of their homes as soon circumstances allowed.141 The 1798 direct tax lists noted three sawmills in the valley, including that of Sylvanus Traves (or Travis) who lived on the farm immediately east of the Hale property. John Traves built a sawmill across the river a few hundred feet downstream from the Hale home. Only six families in the valley had frame homes while less than half of the barns and other outbuildings in 1798 were specifically identified as log structures, suggesting the earliest sawn lumber went to outbuildings.142

When John Comfort’s sawmill began operation at the bend of the river, it was clearly the largest in the region and made lumber readily available in the area. Several decades later, in 1825 Isaac’s sons Jesse and Ward bought the Traves sawmill, and the illiterate John and Mercy Travis both signing their “X” for the transaction.143 Some of the millers, sawyers and workmen of these mills were among the earliest converts to Mormonism.144

Isaac and Elizabeth Hale continued to welcome new babies into their family with the births of a string of girls and Isaac’s namesake boy pressed in the middle. Phoebe was born on May 1, 1798, Elizabeth followed February 14, 1800, Isaac Ward (who went by Ward) on March 11, 1802, Emma on July 10 1804, and Tryal on November 21, 1806.

Hale was not taxed for a barn in 1798. Since he made his living hunting, there was little need to store a harvest of grain and animal feed. There would not be a gristmill within twenty miles for another two decades and the family likely ate little grain themselves. Hale would have needed a smokehouse and butchery to process his regular catch of game, and these were likely the first outbuildings he built after a privy—if he built one—not everyone did in the early years. Even decades later, the Hale men were hired by their neighbors to cut meat, soften it with saleratus, and smoke it for eating in later months. They also dressed, grained, and tanned deer hides for their neighbors. Hale’s sons and a son-in-law, also caught dozens of eel in the nearby river and smoked them for later consumption.145 Most settlers were trying to provide basic needs for their families and built little more than the necessities even two decades after the window tax. William Cope, a young Quaker from a wealthy family in Philadelphia, came through the neighborhood in 1818 on a tour of the remote country, and he observed,

“these people do not seem to value the comforts of a good house as persons in a more cultivated country. They spend whole days in hunting & yet their houses are left in an unfinished state. For instance the scaffolding for building A. Lathrop’s chimney yet remains & looks as if it had withstood many a wintry storm; but the chimney is scarcely raised as high as the roof of his house.”146

Because Cope lived in the city he was more attuned to differences in attitude between the valley’s occupants and “persons in a more cultivated country.” He also viewed hunting as a leisure activity rather than an occupation that left little time for making one’s home fancy, and he clearly overstated his case. But his observation captured a difference in attitude between the working men and women along the Susquehanna River and the gentry in comfortable Philadelphia homes. But the cultural divide was not only due to differences in attitudes about refinement, gentility, and the role of “a good house” in conferring these, it was also partly due to a lack of ownership or attitudes that come with ownership of property in the Susquehanna Valley. Residents changed their efforts toward improving their homes and surroundings dramatically after they gained legal title to their farms. This did not happen quickly.

Tench Francis dictated his will on April 4, 1800, leaving his large tract of Susquehanna Valley property to his wife. While the Hale property changed owners, Pennsylvania sold 9,000 acres of remaining land in the valley to Colonel Timothy Pickering Jr., a Harvard graduate, intellectual, military officer, and politician. George Washington had invited Pickering to negotiate a settlement with the Seneca Indians in western Pennsylvania which the Colonel did with such success that Washington made him Indian commissioner to the Iroquois. Pickering negotiated the treaty of Canandaigua in 1794, and he served as the United States expert on Indian relations until he became Washington’s Secretary of State, a position Pickering held until disagreements with John Adams led to his dismissal on May 12, 1800. After his dismissal, Pickering decided he wanted to retire from public life, move to “the country,” and become a gentleman farmer. When Pickering announced to his friends his plans to move in the neighborhood of the Isaac Hale family, his associates tried to dissuade him from settling along such a remote area of the Susquehanna. “It would be twenty years before forests would become cultivated fields. In that remote region, we cannot conceive the farming will ever be profitable,” a friend wrote.147

Pickering was part of the American gentry and had little in common with the Hale family. When he drew a map of the valley in 1800 it only depicted the frame homes he found there, such as that of Daniel Buck at Painted Rock and John Hilborn at the river’s bend, but not the Hale cabin between those two, or the other log homes of families scattered along the river.148 These backwoodsmen and their families did not receive Pickering’s notice for most purposes. He selected a piece of property in the Susquehanna Valley for what he called his “plantation,” ordered long lists of specific trees and vegetable seed from distributors in England, and hired two men—Isaac Hale and Nathaniel Lewis—to clear part of thirty acres of land during the winter of 1800-1801 in anticipation of his settling the area. Hale and Lewis also built two houses for him, a log one in 1801 and a large, frame, three-story structure in 1805.149 Colonel Pickering drew detailed plans for the home and for a large barn that included specific instructions as to how each space should be arranged and used.150 Hale and Lewis became “the poor neighbors whom he has employed [who] view him with the respect and affection of children to a father.”151

As Isaac Hale reviewed Pickering’s instructions and learned to build the Pickering home, he likely gained experience and ideas he later used in building his own home. While Hale and Lewis worked on the Pickering property, they associated with Colonel Pickering’s son, Tim Pickering. The younger Pickering, a Harvard graduate like his father, resigned his navy commission on May 2, 1801, left Massachusetts on the stagecoach one week later, and eventually walked from the end of the turnpike, through Pennsylvania’s mountains into the Susquehanna Valley and to his father’s land. Son and father prepared for the rest of the family, happy they had escaped the yellow fever in the cities, and anticipating a much healthier climate along the river.152

Isaac Hale worked for the Pickering family over the next few years. The younger Pickering, a man “wont to speak little and to write less,” grew lonesome in the valley, and he began courting Lurena Cole, a sister of Nathaniel Lewis’s wife, Sarah Cole Lewis.153 The well-educated Tim Pickering must have felt out of place within the frontier family of Nathaniel Lewis. But as part of what then existed of an American aristocracy, he immediately gave status to the Lewis and Hale families, a relationship the family still referenced a half-century later. Lurena also became a popular name with future generations of the family. As Tim courted Lurena, and they may have already announced their planned wedding, Isaac worked on the larger, elaborate Pickering mansion. And Elizabeth Hale expected a child again.

Everyone in the valley assisted each other in their daily tasks during social events where this combination of work and play were known as “frolics.” Frolics were occasions for dancing, eating, and socializing while settlers raised barns, husked corn, quilted fabric, or other tasks usually completed as a community. The slave Sylvia Dubois, who worked in the tavern at the other end of the Susquehanna Valley in what became Great Bend Township, often served “great numbers of hunters and drovers” who came to the tavern from 1803–1806. The hunters came to trade, “to sell deer meat, bear meat, wild turkeys, and the like, and to exchange the skins of wild animals for such commodities, as they wished.” She remembered they often had a good time. “We’d hardly get over one frolic when we’d begin to fix for another.”154 Settlers held a big frolic on Wednesday, July 4, where they enjoyed dancing and eating as they worked together while honoring Isaac Hale and the other men in the valley who had served in the Revolutionary War. Elizabeth Hale delivered a daughter the following Tuesday on July 10, 1804, and named her Emma—a name then popular in both the United States and Great Britain but with no apparent family connection. It is possible that Hale’s role in working for the well-read Pickering family encouraged them to suggest names for his daughter.

Two days after the baby’s birth, Colonel Pickering’s good friend Alexander Hamilton was killed in his famous duel with Aaron Burr. Several of Pickering’s friends had purchased large tracts of land in the Susquehanna Valley from him; and those friends combined the properties together and gave them as a gift to Hamilton’s widow for her family’s support.155 Through this means Elizabeth Hamilton briefly became owner of a significant portion of the Hale neighborhood. Hamilton divided her land into affordable lots and sold them to new settlers which increased the population of the valley. The Pickering family continued to hold onto most of their land, however, and Hale worked for them alongside Colonel Pickering’s young son, Tim. The twenty-three-year-old Tim married twenty-three-year-old Lurena Cole, on December 29, 1804.156

Just as Isaac Hale and Nathaniel Lewis finished building the large Pickering mansion, Lurena Cole Pickering and her husband Tim, along with Lurena’s mother (Nathaniel Lewis’s mother-in-law), moved into it.157 Lurena delivered a son, Charles Pickering, November 10, 1805. Young Emma and Charles were briefly raised within the same extended family until Charles left the valley with his mother. He eventually studied at Harvard like his father, became a member of the Philadelphia Academy of Natural Sciences in 1827, was elected a member of the American Philosophical Society in 1828, and became a leading American naturalist. Charles Pickering became America’s leading polygenist, a scientist who believed that different races had been created separately—eventually publishing his book Races of Man and Their Geographical Distribution.158

Tim Pickering grew increasingly ill after his marriage to Lurena and the birth of his son. A gaping hole grew in his neck, and he became emaciated until he looked like a living skeleton.159 The Lewis family moved into the Pickering log home to better care for him. Colonel Pickering sought the advice of Benjamin Rush, formerly surgeon general in the Continental Army, and other prominent physicians who diagnosed Tim as having throat cancer. Then the elder Pickering came back to the valley to take his son away for better medical treatment.

When he arrived, Colonel Pickering wrote to his son Henry that Nathaniel Lewis, “who has been much used to sick persons, and whose experience enables him to judge better than I, thinks your brother not likely to survive three days longer.”160 Tim Pickering mentally prepared to die in good nineteenth-century fashion with a “serenity of mind, flowing from a sincere and constant endeavor to preserve a conscience void of offence toward God and toward man!”161 Lewis was right and his brother-in-law died three days later on May 14, 1807.162 Isaac Hale helped bury him on the brow of a hill “between the mountain and Starucca [Creek].” “On the day of his burial,” Colonel Pickering wrote of his son, “I intimated to Hail and Lewis my wish that flat stones might be set up at his grave. They seem to have thought of it. ‘We will do it,’ said Hail; ‘we will fix the stones, so that Charles, when grown up, if he should come this way, may find the spot where his father’s body was laid.’ These words were uttered with so much affection and respect for the deceased as showed how greatly your brother was beloved.”163 Colonel Pickering wrote to his son Henry, “Mr. Lewis and family have, for two months, lived in the small house we built in 1801. . . . When we are gone, his family will move into the other house.”164 Pickering took Lurena, who was then pregnant with her second son, Edward, and the young Charles back to Salem, Massachusetts, to live. The sons likely visited their father’s grave at some later point and replaced the original Hale and Lewis marker since a nicely carved 1820s headstone with a weeping willow and well-carved lettering now marks the grave.165

Religion in Hale Family

Congregationalism

A religious transformation in the Hale family followed the death of Tim Pickering; and a transformation in the Hale home and land followed their religious transformation. This did not happen, however, until the family already had considerable religious experience. When Isaac and Elizabeth Hale settled the valley, they had only nominal religious involvement. A Congregational minister traveled through the region in 1789 and appointed Daniel Buck as the local pastor. Buck served as the first permanent minister stationed in the Everlasting Hills.166 He found success in his attempt to spread religious conviction, and he developed a congregation downriver eight miles from the Hale home. He established another congregation about ten miles upriver from the Hales in South Bainbridge, New York, and found success in other valleys in the region. When a visiting minister came to the Susquehanna Valley to observe Buck’s congregations in December of 1797, he noted local excitement over religion had increased significantly in the previous few years and wrote in his journal, it “looks like the beginning of an awakening.”167

Jonathan Edwards’ encouragement to have boys like Buck brought up speaking local Native American languages was an outgrowth of the First Great Awakening that spread across the nation more than fifty years earlier as religious excitement sparked in congregations of religiously involved citizens, but then slowly cooled. This local “awakening” had more in common with the Second Great Awakening that would begin in a few years, however, since it attracted the unchurched in the area until “nearly all the families” in the valley offered morning and evening prayers.168 Both the Hale and Lewis families were caught up in this awakening, and the parents took their one-year-old sons, Alva Hale and Levi Lewis, to Buck for baptism.169

John B. Buck, a grandson of Daniel Buck, recalled years later, after the valley’s Congregationalists had transformed themselves into Presbyterians, how during the 1790s the congregation

was scattered up and down the river, in cabins. The only means of getting from here [at the log church house eight miles downriver from the Hales] was by canoes. They went as far as the rift or rapids, where they left their canoes, and walked past the rapids, then took passage in a large canoe around by my father’s. For dinner, they carried milk in bottles, and mush. They listened to one sermon in the forenoon, and then came back to the canoe and ate dinner, then went back to second service; Daniel Buck was minister. In summer this was their means of travel. With increase of families the means of communication increased. In winter there was no other way save by foot-paths. For many years there were no denominations save Presbyterians [Congregationalists].170

This early religious “awakening” in the valley did not last long because of what became known as the “Buck difficulty” in 1799. During that year, Buck was charged with teaching false doctrine, leading some members of his congregation to try removing him from his position. He began focusing on the Old Testament rather than the New for his teaching, and his parishioners accused him of “preaching immoral doctrine” along with claiming “the doctrine of faith was not found in the Old Testament and that a ‘conscience’ was not a natural faculty, but the result of education.”171 Although Buck continued to serve until his death in 1814, the congregation struggled for the rest of his tenure.172

The Hale and Lewis families were apparently influenced along with others by the Buck difficulty, and withdrew from his congregation—although it is not clear if it was the “immoral doctrine,” issues of faith, those of a conscience, or all of these that offended them. The only child of theirs to be baptized after the controversy began was Isaac and Elizabeth’s daughter Emma, who was baptized by Buck not long after her birth in 1804, just before Methodism arrived in the valley.173

The slave Sylvia Dubois attended the same congregation where Emma was baptized and described it as “the Calvinistic faith . . . the Old School Presbyterians,” and consequently tended to adopt an attitude of fatalism. Dubois believed, “‘Tain’t no use to worry—it only makes things worse. Let come what will, you’ve got to bear it—‘taint no use to flinch. Providence knows best—He sends to you whatever He wants you to have, and you’ve got to take it and make the best of it.”174